The Universal Design for Learning Guidelines have seen tremendous momentum in adoption by the educational and academia capacities in recent years. However the COVID-19’s appearance in 2020 has rocked the world and in turn; sent the Universal Design for Learning Guidelines (UDL) into the limelight. Prior to the COVID-19, the UDL have played an integral part of educational course planning by educators for students from K-12 to post-secondary schools, and the UDL slowly evolved and improved-on over time. In the current day in age, the true effectiveness of the UDL guidelines are put to the test in all educational environments as in-person lectures and webinars are all hurriedly converted to online web-based courses.

My prior exposure to online-based learning dates back to high school. During that time, high school courses from grade 8 to 12 are offered to students who have failed certain courses. Students are offered remedial options to re-attempt the course via online-learning. Interestingly, I was at the time looking to take advanced grade 11 courses while enrolled in grade 10. As a result, I had an early exposure to the emergence of online based courses; along with their pros and cons. It is important to note that I was unaware if the web-based courses were created in tandem to the UDL guidelines, therefore I cannot comment on the effectiveness of what was offered to me. While taking the courses, it was mandatory that I regularly check-in with my teachers/instructors of the course via telephone, email, and in-person site visits. This ensured that instructor and students are adhering to online learning guidelines.

Fast-forwarding to the recent times, web-based delivery of course have been accepted as the norm by both instructors and students alike. However, I have noticed slight difficulties in effective communication during this fast period of transition. Taking an example from a recent course taken via Thompson Rivers University (TRU), it easily depicted many struggles that educators and students that had to endure. The Math course via TRU has traditionally been taught in lecture-based classes, but with the fast changeover to online-based delivery, my instructor for the course struggled to video his lectures of the math concepts. In turn, when I had contacted my instructor for math-problem explanations, I was instead provided with Youtube links to explanations that I had to figure out myself other than the provided math textbook. The aforementioned difficulties in communication was clearly evident when the teacher announced quiz and exam dates in Moodle; rather than via email. This caused some inconsistencies in notifications and many students were not made aware of deadlines and due dates.

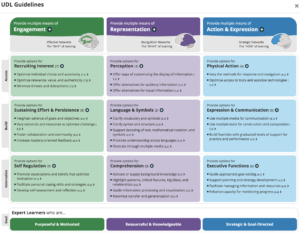

Figure 1. Summarized table of the UDL developed by CAST

In the course readings as provided on the UDL principles, I strongly feel that my prior experience with the math course with TRU can be greatly improved-upon with stronger course design and guidelines. Some of the improvements include enhanced communication methods, course-work guidelines, and math concepts delivery. Preceding to the course readings this week, I am unfamiliar with UDL principles. However, after careful studies of the UDL principles as developed by Cast in Figure 1, I was able to see how the guidelines are interconnected to provide clear guidance. The principles of providing different means of engagement can easily include the incorporation of technologies like ZOOM to deliver online discussions between instructor and students (Dickinson & Gronseth, 2020). Looking at the means of representation in the chart, it reminds me of the adopted tool of Brightspace, as it provides a central hub for students to access coursework deadlines, syllabus, and course related materials. Coursework design does not need to adhere 100% to the UDL principles in the Table 1, however it needs to embrace the concepts and become baked into the underlying of the course design.

I am a strong believer that over time, the courses offered in Brightspace will be improved upon with feedbacks of students, to provide a very easily accessed central hub for information on coursework delivery. In the realm of IT, it is often know as the “single pane of glass” model; because it allows an easy flow of information that can be recorded and accessed by the user base. The UDL principles is a powerful layout for both current and future online course delivery design!

References

Crosslin, M. (2018). Effective Practices in Distributed and Open Learning. https://uta.pressbooks.pub/onlinelearning/chapter/chapter-5-effective-practices/

Dickinson, K. J., & Gronseth, S. L. (2020). Application of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Principles to Surgical Education During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of surgical education, 77(5), 1008–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.06.005

“The UDL Guidelines.” UDL, 6 Oct. 2020, udlguidelines.cast.org/.